Even today it is impossible to conceive the visual history of the American West without Edward Curtis’ ‘The North American Indian’, an ambitious project that documented the life and culture of eighty Native American peoples. Curtis spent thirty-seven years on the field where he photographed, documented, and sought to reconstruct life on the North American West of Mississippi, as he believed it to be before the White Man arrived.

An experienced photographer and probably influenced by the role of photography in anthropological fieldwork, Curtis started this project in 1904 to create an exhaustive record of indigenous peoples and cultures before they vanished. More than a mere photographic documentation project, this anthropological enterprise was vaster than that and, besides the images, involved the recording of songs and oral testimonies about myths and folklore.

What resulted from this work was an impressive work of 20 volumes of text accompanied by 1500 photogravures, 20 complete portfolios and a special deluxe edition, published between 1907 and 19301. In 1910, the New York Herald wrote that this was “the most gigantic undertaking in the making of books since the King James edition of the Bible.”

I

In 1899, at the invitation of a leading group of scholars, Edward Curtis leaves as a photographer on an expedition to Alaska, directed by George Bird Grinnell. Besides editor of ‘Forest and Stream’ magazine, Grinnell was the author of several Native American studies, and it is at this moment that Curtis begins his serious and conscious photographic work on the life of the Indians.

The following year, still at Grinnell’s invitation, Curtis spends the summer in northern Montana, where he is surprised by the natural beauty and apparent low contamination through contact with the White Man. Immediately Curtis realized that this idyllic image of man in contact with nature was rapidly deteriorating among the Indians and commenced to document the harmony of this almost sacred place of unity between Man and Nature and with which modern civilization had lost touch.

Curtis funded the start of the project until 19062. In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt is impressed by one of the first exhibitions of Curtis’s work in Washington, DC, and feels that the project of photographing about eighty North American Indian tribes should be properly supported and funded3. Shortly after, Roosevelt introduces Curtis to J. P. Morgan, literally the richest person in the world who, after an initial hesitation, agrees to work with Curtis and proposes that the photographs and texts should be collected and displayed in a more permanent way. In 1906 Morgan created “The North American Indian, Inc.”, a subsidiary company of the Morgan Bank which handled subscriptions, invested funds ($15,000 annually for five years) and dispensed financial support to Curtis.

Other patrons included the railroad tycoons E. H. Harriman and Henry E. Huntington, U.S. Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot and other government officials, several bankers, and Andrew Carnegie and a variety of other prominent industrialists (Gidley, 1984, p. 181).

The first volume was published in 1907, with a foreword written by President Theodore Roosevelt and the editor of the text was the ethnologist Frederick Webb Hodge from the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology.

Documents and artifacts were collected and systematically photographed4. Curtis led a small team that previously researched each one of the tribal areas west of the Mississippi. This was followed by photographic expeditions that covered the most relevant points that research had highlighted. A project of this scale and with this scope required the help of a team of ethnologists, photographic assistants and informants.

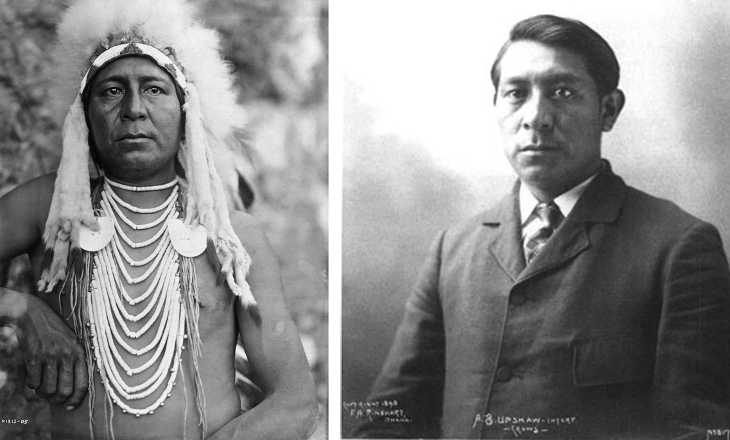

Besides ethnographer William E. Meyers, who was the main writer of the project, and Frederick Webb Hodge, Curtis also had help in the field from native informants George Hunt and Alexander B. Upshaw.

In 1911, financial difficulties forced Curtis to hold a series of conferences hoping they could stimulate new subscriptions. Musical interludes of Indian music played by an orchestra accompanied these illustrated lectures, narrated by Curtis. While this was a huge endeavor for Curtis, who preferred to be working on the field, he brought an Indian opera to the stage of the Carnegie Hall in New York City, took his lectures to universities and museums, and in 1914, he even produced a full-length movie starring Indian actors5.

Photographic illustrations were produced using photogravure and were selected from over 40,000 photographs taken between 1897 and 1930. Each of the volumes took between one and two years to produce. Five hundred copies were printed, but only 272 were bound. The cost of a subscription to volumes and portfolios was $3,000.

The North American Indian was significant not only as a publication but also as a cultural phenomenon. It constituted a huge repository of ethnographic information systematically organized according to the best practices of the time and accessible writing and described social organization structures, myths, rituals, vocabulary and languages, biographies and much more. But this depiction of the Native Americans – at this time with a shrinking population, deprived of resources to cope with white expansion and unable to adapt to some new imposed dynamics – should not be viewed as true. This representation had political, economic, ideological and aesthetic determinants. It has been conditioned and, in turn, conditioned the attitudes of the dominant culture. Allowing for an ambiguous interpretation, President Roosevelt described the project as a “real asset in American achievement.” The nationwide project eventually relates, directly or indirectly, to most of the policies implemented by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. which, from this distance, have proved extremely harmful at all levels to Native peoples.

II

From the beginning, Curtis became very aware of the Native American conception of life that denied the separation of material and spiritual and saw opposites in a continuous flux. From this awareness, he realized that this conception was on the verge of extinction and, consequently, started to accurately document the global spectrum of Native American life. Although Curtis was an amateur who lacked the academic background, formal perspective, and scholarship of an anthropologist, this deficiency was partially offset by his direct access to primary sources and his first-person accounts.

Historian Louis S. Warren writes that the “notion of Indians as ‘Nature’s children’ never had a better publicist than Curtis, and if Indians were timeless and natural, there could be little doubt they would disappear before people of progress and industry” (Warren, 1999, p. 362)

Indeed, cultural traditions were disappearing but not because of their inability to adapt to progress. In the early years of the twentieth century, indigenous populations were forcibly being assimilated by the American federal government after decades of violent eradication and seizure of land. Contrary to these policies of detribalization, Curtis tries in his images to hide the signs of deculturation, pursuing the ambition to find the Indian before contact – the exotic, preindustrial and pre-modern Indian, and to a large extent the subject of enormous fantasy. We owe him, therefore, an extremely elaborate and sometimes heavily staged photograph, marked by a powerful imagination. In American Art, art historian Shannon Egan (2006, p.80) states that “[d]espite Curtis’s activism on behalf of the southwestern Indians’ political situation, he suppressed the plight of the ‘real’ Indians and replaced it with a narrative of Indianness that served the artistic and political needs of an Anglo-American culture.” His multiple pose-setting strategies and the use of accessories bring his photography closer to mixed, creative, or interventionist practices.

Since the moment of its publication, the critical analysis of this work is divided around the problematic between truthfulness and falseness, oscillating between a primary credulity (idolatry) and an almost paranoid obsession with the false (iconophobia) (Arrivé, 2012, p. 2).

III

“While primarily a photographer, I do not see or think photographically; hence the story of Indian life will not be told in microscopic detail, but rather will be presented as a broad and luminous picture.”

(Curtis, 1907, vol. 1, p. xxv)

From this distance, the greatest challenge remains to understand a structural paradox in Curtis’s work: the quest for the truth through the use of the artifice, in the convergence between art and science. The photographs, which often depict people who were actually reconstructing for the camera ways of life that no longer existed, are received, but not always understood, within this founding ambivalence. Sometimes they are considered authentic and sometimes they are seen, and condemned, as obvious falsifications.

In Curtis, truth has less to do with cultural purity, photographic authenticity, or ethnological truth than with the conformity of his photographs to the canonical images of the primitive imagination. His scenography is based on the imitation of a “déjà vu” and on meeting the expectations of the public of the time (Arrivé, 2012, p.2).

This truth that Curtis pursues, and which is openly defined as an act of fabrication, is then paradoxically materialized through manipulated images. However, this distancing of Curtis from reality is, according to him, only to be more faithful to the idea.

Curtis opens the first volume of The North American Indian with a very significant image and that, besides setting the tone of the dialogue between his photographic language and his belief that the Native Americans were a vanishing race doomed to extinction and were in urgent need for recording and memorialization is a paradigmatic example of Pictorialism (Gidley, 1994, p. 182).

This photograph, “The Vanishing Race” (1904), shows a line of Navajos riding away from camera towards the shadows of canyon walls. Its caption reads “The thought which this picture is meant to convey is that the Indians as a race, already shorn in their tribal strength and stripped of their primitive dress, are passing into the darkness of an unknown future. Feeling that the picture expresses so much of the thought that inspired the entire work, the author has chosen it as the first of the series” (Curtis, 1907, Portfolio I, Plate no. 1).

In these early years of the twentieth century, while enjoying great popularity, Curtis saw his photography praised by the photographic community. His work has been appreciated and exhibited by Alfred Stieglitz6, a central figure of the Pictorialist Photo-Secession movement in the US. Following the Pictorialist rules, Curtis applies the procedures of studio photography to in situ scenes and portraits in a staged and almost theatrical way. Before taking a photograph, he writes a script and shapes the real through carefully rehearsed poses, using very careful lighting techniques or employing accessories. Curtis also intervened in the negatives, reframing, manipulating, eliminating details or even drawing elements that were not present at the moment the picture was taken. These interventions seek, above all, to find the “Real Indian”. Despite the elegiac tone, the images were deeply respectful of the Native American People, always presenting them with dignity and pride.

“None of these images should contain the slightest trace of civilization, whether it be a garment, an element of the landscape or an object on the ground. These images were designed as transcripts for future generations so that they would have as accurate a picture as possible of the Indian and his life before he had any contact with a pale face or even that he does not suspect the existence of other men or worlds different from his” (Andrews & Curtis, 1962, p. 26).

Much has been written about this tense relationship between truth and reality in the work of Edward S. Curtis. In a famous 1910 photograph, “In a Piegan Lodge,” a small clock appears between the two seated men. In a later print, the clock was deleted, probably because it would seem too contemporary. This change is one of the most obvious of the project, but Curtis has always eliminated any elements that didn’t fit his “noble savage” vision.

In many other cases, the photographs were fully staged, as in “The Old Cheyenne” (1911), where the ancient rider displays an obvious human scalp, many years after the Plains Wars ended and these peoples already lived in reservations.

Shamoon Zamir illustrates this approach by using a portrait that he calls “an illustration of the triumph of romance over reality, genre conventions, and racial typology over individuated portraiture” (2007, p. 615). In this photograph of Alexander B. Upshaw – Curtis collaborator and Crow interpreter – instead of showing him in the western clothes he daily wore, Curtis photographed him in a feather headdress and bare chest.

The truth that Curtis pursues is openly defined as an act of fabrication, and it materializes itself, paradoxically, through openly manipulated images. However, when Curtis distances himself from reality it is, he says, just to be more faithful to the idea. This paradox that Curtis works on is underlined by President Theodore Roosevelt in the preface to the first volume of ‘The North American Indian’: “In Mr. Curtis we have both an artist and a trained observer, whose pictures are pictures, not merely photographs; whose work has far more than mere accuracy, because it is truthful” (Curtis, 1907-1930, vol. 1, p. xi)

Edward Curtis distinguishes himself from other Pictorialist photographers in claiming to establish the validity of his images in two regimes of truth combining artistic idealism with Victorian science. It is this twofold relationship that leads him to incorporate an ethnographic observation with pictorial interpretation, the aura of art with the authority of science. To be fair, manipulation, reconstruction, and the use of staging in photography were still often considered valid ethnographic strategies by museums and the Bureau of American Ethnology in the early twentieth century (Arrivé, 2012, p. 4).

Curtis would later confess that with the Navajos, these reconstructions of ceremonies and rituals had shaken traditional beliefs within the tribes themselves and led to some divisions among their members.

In a moment marked by criticism of his interpretative approach, seen as artistic, Curtis seeks to establish its legitimacy. On one hand, thanks to the political trust of President Theodore Roosevelt and, on the other, thanks to the intellectual security of Frederick Webb Hodge of the Smithsonian, who acts as a reviewer and editor of the project, contributing largely to his eligibility in the academic circles of the Bureau of American Ethnology, joined by anthropologist G. B. Gordon who writes in one of his reports in the ‘American Anthropologist’:

“Indeed, there has never been seen a series of pictures from brush or camera which so artistically and at the same time so accurately illustrates the life of the Indian tribes living within the United States, or which portrays so truthfully the physical types characteristic of these tribes” (Gordon, 1908, p. 435).

IV

After analyzing Curtis’s complicated and tense relationship with truth, we will propose a historiographical revision distinguishing several moments: a “modernist” moment of marginalization; a “popular” moment of iconization; a “postcolonial” moment of reappropriation; and finally, a moment that we will call “post-revisionist” (Arrivé, 2012, p. 4). Therefore, it will be necessary to get out of this dichotomy between true and false to propose a new heuristic to explore other aspects.

While it can now be admitted that Edward Curtis did not stage his photographs with the intention of misleading and given the central role they played in the way society looked at Native Americans, it is important to realize that the way they were viewed has varied greatly over the last hundred years. Applauded in the 1910s, neglected in the 1920s, literally forgotten between the 1930s and the late 1960s, acclaimed in the 1970s, rejected in the 1980s, before being collected and plentifully exhibited since the 1990s, Edward Curtis’ work follows an errant and discontinuous course. The spectrum of this critical trajectory illustrates the variability and fragility of truth discourses, but it also emphasizes the need to move away from this analysis in order to explore new approaches.

In the period between wars – the time when straight photography was born – it would not be surprising that Edward Curtis’s interventionist practices were devalued by the New York circles, considered obsolete or unphotographic7. The hybrid and inter-iconic practices of Pictorialism thus appear as a return closely bound to Europe, to the Beaux Arts and the literary and pictorial tradition. While clarity, sharpness and impersonality become the benchmark, we do observe a great change in the trajectory of photographic truth, which now undergoes a de-subjectivation moment itself.

Curtis was eventually not only marginalized by the Stieglitzian avant-garde, but was omitted from photography’s histories, in particular Beaumont Newhall’s and his hyper-formalist views. Despite the difficulty of considering an ostensibly ideological corpus from a strictly aesthetic point of view (at the risk of giving an aestheticizing reading), some art historians have nonetheless attempted a more formalist or iconocentric reading by analyzing the pictorialism of Curtis in its technical and stylistic dimensions, removing cultural issues in strictly formal considerations (Arrivé, 2012, p. 6).

After a long phase of oblivion between 1935 and 1971, Curtis’s photographs reappear in two exhibitions at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York and the Museum of Art in Philadelphia in 1971 – these are the first entirely dedicated to the author since his death in 1952. These exhibitions mark the beginning of the “Curtis’ renaissance” and a series of shows, accompanied by a strong editorial activity and the publication of several monographs. In the context of the civil rights movement, Curtis’s photographs are regarded as the last direct testimony of a Native America (McLuhan, 1972) and are often used as primary sources in television documentaries or in the press. This perspective, which we may consider idolatrous, ignores the manipulation part of the Pictorialist project and unreasonably naturalizes the content of Curtis’s photogravures by confusing image and referent.

The popular enthusiasm of the 1970s also corresponds to an effort to re-qualify Curtis’s photographs, pursuing a logic of value rather than a logic of meaning. Its symbolic value within popular culture and its market value (from low-priced industrial reproductions to original images sold at auction at exorbitant prices) also adds to the heritage value of his work when a cycle of traveling exhibitions is organized outside the United States8. Strangely considered simultaneously works of art and documents of civilization, Curtis’s images, shown in Europe and Asia, are seen as a national heritage in a tribute to an Indigenous America.

In a cyclical movement that oscillates between acceptance and refusal, so typical of so many moments in art history, the ‘credulity’ hitherto evoked radically reverses itself in the early 1980s, as victim of a de-sacralizing critical and iconoclastic revisionism, which denounces Curtis’ photogravures as deceptive manipulations and his stagings as products of transgression and manipulation. It is now, at a time when the history of the American West intersects with nationalism, that The North American Indian meets its fiercest critics. These readings take place in the context of an iconophobic inspirational sensibility centered on the texts of Michel Foucault, Theodor Adorno, Susan Sontag, Jean Baudrillard or Paul Virilio and where, from the notions of spectacle and simulacrum, the image is seen as “misleading”, “lying” or “dissimulating”.

While the iconoclasm of the 1980s offered a counterpoint to the hagiographic and idolatrous reviews of the previous decades and greatly contributed to a necessary “revision” of the mythology of the American West, this critical stance also contributed to stigmatize the creative dimension of the photographic act (and its component of inherent imagination). The moral and normative problematic of the truthfulness and the falseness relegated the North American Indians to the narrative of ethnohistory, continuing to refer to concrete concepts of authenticity, veracity and purity (where purity is often confused with photographic truth).

We can even say that this Edward Curtis ‘trial’ is also a symptom of the tension in the human sciences around the question of subjectivity, especially in anthropology. Forgetting that documentary photography and reportage itself, at the time, are also undergoing an identity crisis, what most disturbed critics and scholars in Curtis’s work was without doubt the way he combined the expressive use of photography with a projective and interpretive practice of ethnography.

Never before have idolatry and iconoclasm come together so intensely on the same subject matter. Although these two approaches may seem contradictory, they are simultaneously the two sides of the same literalism in an attempt to establish as a single standard of photography their faithfulness to the referent, regardless of the way photographs are produced.

The trend of the most recent analysis of Curtis’s work is to try to re-contextualize the photogravures in their original editorial environment, that of the book-object that semanticizes them. Although ‘The North American Indian’ has already been studied as a work of art, text and project, it seems imperative to explore it as an editorial, symbolic, rhetorical, identity and ideological device, in a non-compartmentalized multi-disciplinary perspective that considers its pragmatics, its politics, its epistemology and its poetics.

It is in this contradictory synergy that images gain meaning and that ‘The North American Indian’ can offer us an overview of their discontinuities, in the convergence of political history, the history of the American West and nationalism with the history of ideas, representation and knowledge.

References

Andrews, Curtis, & Curtis, Edward S. (1962). Curtis’ western Indians.

Arrivé, M. (2012). Par-delà le vrai et le faux? Les authenticités factices d’Edward S. Curtis et leur réception. Études Photographiques, 29.

Curtis, E. S. (1907-1930). The North American Indian.

Egan, S. (2006). “Yet in a Primitive Condition”. Edward S. Curtis’s North American Indian. American Art, 20(3), 58-83.

Gidley, M. (1994). Pictorialist Elements in Edward S. Curtis’s Photographic Representation of American Indians. The Yearbook of English Studies, 24, 180.

Gordon, G. (1908). The North American Indian. By Edward S. Curtis. American Anthropologist, 10(3), 435-441.

McLuhan, T. (1972). Touch the earth; a self-portrait of Indian existence. New York: Pocket Books.

Trachtenberg, A. (1980). Classic essays on photography. New Haven, Conn.: Leete’s Island Books.

Warren, L. S. (1999). Vanishing point: Images of indians and ideas of American history. Ethnohistory, 46(2), 361-372.

Zamir, S., Upshaw, A., & Curtis, E. (2007). Native Agency and the Making of “The North American Indian”: Alexander B. Upshaw and Edward S. Curtis. American Indian Quarterly, 31(4), 613-653.

Notes

- Curtis’ benefactor, J.P. Morgan, who funded the project insisted that books should be sold through a subscription and that their price should be high. Because of this option, only the richest had access to ‘The North American Indian’.

- Some of his early photographs would eventually win the Grand Prize in the National Photographic Exhibition held in Washington, DC in 1908, and were then exhibited and awarded internationally.

- President Theodore Roosevelt also commissioned Curtis to photograph his family and his daughter’s wedding. Some portraits used in Roosevelt’s self-biography years later would also be by Curtis.

- Besides the photographs over 10,000 wax-cylinder recordings of language, music, and tribal lore and histories were collected.

- Tragically titled “In the Land of the Headhunters” (1914), it is a love story starring Kwakiutl actors. The movie was a financial disaster but was re-edited in 1974 and re-titled “In the Land of the War Canoes” by George Quimby at the University of Washington.

- Alfred Stieglitz (1864 – 1946) was an American photographer and modern art promoter instrumental over his fifty-year career in making photography an accepted art form. Besides his photography, Stieglitz was known for the New York art galleries he ran in the early part of the 20th century where he introduced many avant-garde European artists to the U.S.

- Stieglitz refers to the process used by Curtis as “unphotographic”.

- Newhall doesn’t mention Curtis on his ‘The History of Photography’, from 1964. Only in its fifth edition (The History of Photography, Completely Revised and Enlarged Edition, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1982) Curtis is referred in one paragraph on the improbable chapter ‘The Conquest of Action’ (ibid., p. 136).